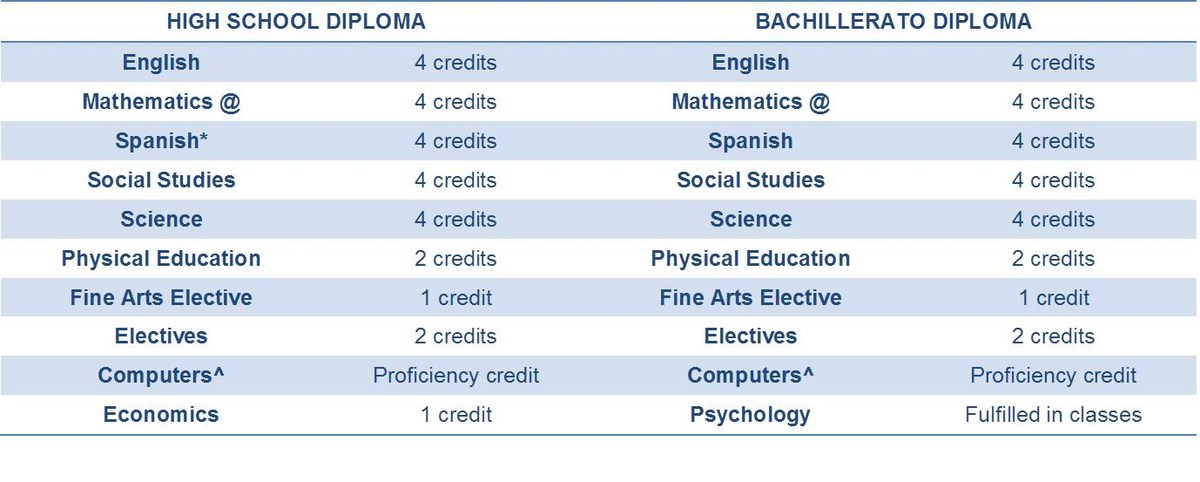

For many years, even when I was very young, I dreamed of going to college in the United States, to get a liberal arts education. My school was a bilingual K through 12 school in Bogotá, Colombia, where we were expected to complete the requirements for a United States high school diploma and a Colombian bachillerato one, too. This dual culture laid bare the essential differences between one educational system and the other. For the high school diploma, we had to take 22 classes in high school, spread out over the four years. Meanwhile, the bachillerato degree went beyond, expecting the successful completion of 29 classes in the same amount of time.

Those seven additional classes we had to take to fulfill the Colombian Ministry of Education’s bachillerato program included subjects like physics, philosophy, and world history, things we’re not exposed to until college here in the U.S. The idea behind this kind of curriculum is to make students aware of where their strengths and challenges lie, to help them figure out their preferences for one career track over another early on, so by the time they arrive in college, they can start to follow an already-focused path.

Perhaps there is a greater urgency in Latin America and other places around the world to produce ready workers in specialized fields. Or maybe it’s related to the scarcity of spots in universities and the vast amount of work students must invest to qualify for one of them at excellent but insufficient institutions of higher learning. This is the case everywhere from Europe, with its venerable, public universities to the developing world, where private universities are there to absorb the demand for a career path but are often outside the financial reach of many.

The result is that once a student chooses a particular line of study, she will have to stick to it. To switch majors is the equivalent of having to begin again if say you realized you couldn’t stomach medicine and wanted to study law instead. There are also far fewer opportunities to supplement a major with coursework in other fields. In my case, my high school experience had already clarified the areas that interested me and the ones that didn’t, but anytime I tried to translate what my favorite subjects would clearly lead to, I would come up with a multi-part answer. In Colombia, I could study literature. Or I could study law. Or I could study linguistics. Or I could study political science. I wanted so badly to dip my toe in all of them.

Here in the U.S., students can major in one thing and minor in another. If they work hard they can double major and they can go on to further specialize via graduate or professional school. The United States comes in second in a list of countries with the greatest number of colleges and universities, preceded only by India, which boasts 4 times the population. The more colleges, the more people will go to college, and it has become a common piece of the American trajectory, with young people taking out debilitating loans to make sure they get their higher education. While greater percentages of educated and specialized citizens benefit the progress of a nation, the stakes today are higher than they were all those years ago when I was dreaming of mixing up my ideal semester.

Certainly, the high cost of higher education comes into play when considering a career these days. Few would be thrilled to go into years of debt without some hope of a career lucrative enough to get them back out of the financial hole and prosper. For this reason, a lot of the subjects I was so passionate about as I prepared to apply to college are some of the least popular today. Humanities, the arts, pure maths, and social sciences inevitably suffer in this age of costly colleges and careers that are no longer a result of being a well-rounded individual, but a highly focussed and motivated one. When I tried to look up a list of college majors that are less desirable today, my search engine suggested the phrase “which college majors are worthless.” Even the Google algorithm first associates value or worth with an education.

Less interest in majors like history, performing arts, fashion design, archaeology, psychology, art history, journalism, math, and literature reduces the size of these departments at universities, which, with less funding can hire fewer professors, which in turn creates less demand for these majors. Such is the vicious cycle. The less value we assign to something as a society, the fewer people will want to enter that field, until the existence itself of that field begins to flicker, like a ghost of a different time.

Time is the other serious consideration, beside the aforementioned money, when it comes to selecting a career. Today, from primary through high schools, principals and heads of school talk about the careers of the future that awaits the newest generations, some of which we haven’t even dreamed yet. Experts, like Jack Kelly at Forbes, can predict certain trends, though, both through the already observable evidence of each new batch of college graduates and by translating current trends into a premonition of the general shift that is already taking place. Some of it is heartening and some of it is quite disturbing to consider. Kelly himself calls it dystopian.

For instance, the amount of damage we have done and continue to perpetrate onto our planet indicates that environmental scientists will continue to be coveted specialists, problem-solvers who might be able somehow to swoop in and save us from ourselves. Similarly, the vast advances in medical technologies indicate that life expectancy will continue to skew older so that those in the business of caretaking and healing the elderly will be in high demand. Advances in science in the realm of artificial intelligence and robotics indicate that each decade will find a way to mechanize more of the industrial process until blue-collar work will disappear. White-collar work, too, is under siege as digitizing corporate systems begin to make the middle-people and paper trail drones of corporate America obsolete.

Studies show that engineering (of all kinds) continues to be a good field to enter in terms of job prospects and decent salaries. The same goes for the careers that work directly with money directly (finance) or even abstractly (economics, marketing). Naturally, all of the technological applications are expected to prosper in a world that grows ever more dependent on computers and social media. This start-up/communal workspace/entrepreneurial vibe to today’s job market is so palpable that even online quizzes designed to help students zero in on career choices probe the test-taker more on abstract concepts that belong on office inspirational posters than on concrete questions like their favorite subjects or greatest dreams.

The moment we are living is a big reason why the attractiveness of a particular career might be in question right now. Most career surveys tend to focus either on the profitability factor or on the innovative nature of the job and its feasibility for the future. Despite taking a totally different lens to view the issue, inevitable many of these overviews conclude with identical observations. Only careers that remain viable in these times of dramatic change in the ways we conduct business, in the shape of the marketplace, in the currency that certain knowledge holds could possibly be lucrative. How can I combat skill obsolescence? How do I ensure I earn enough to support myself? At the end the two questions are one and the same.

As you are probably imagining, the methodology I personally used, deferring the moment of having to settle on just one track as long as possible, taking courses in as many diverse subjects as my whims inspired, is not the prescribed approach by too many college counselors today. STEM subjects are overwhelmingly the darlings of the future because so much of progress is measurable on a technological scale. But what if you are like me, and these subjects, endlessly fascinating as they are and enviably practical, too, are not your forté? Does that leave us all out of the new order?

The first thing to remember is that a major does not always equal a career. There is an argument to be made for the way in which being a student teaches us how to think and problem solve. Good college counselors might advise a soon-to-be high school grad to focus on the majors that obviously gear you toward a lucrative, future-reaching career, but giving yourself the opportunity to explore the subjects you truly find fulfilling can be a much better education. Not only will you be far more motivated to excel, but you might even stumble onto something novel and original this way, rather than struggling to keep up with the herd.

The trends in college majors over the last decade have demonstrated that while yes, profitability and future viability have indeed had an impact on the careers that grads gravitate to, making formerly hugely popular majors like English drastically decline in numbers, students are still, by and large, studying the subjects they are passionate about. Psychology and teaching, for example, though not amongst the most lucrative careers and long undervalued in our society, still occupy top spots in students’ choices. Together with health sciences, physical sciences, and law, these fields are top picks, from undergraduate majors all the way through master’s and doctoral programs.

And thank goodness for that! Knowing how to teach is one of the most adaptable and transformable skills a person can have. It necessarily includes public speaking, operational strategies, managerial skills, interpersonal skills, plus whatever the knowledge of the subjects taught, plus the kind of neuro-flexibility to quickly learn new material to teach. People in the field of education to stay on the vanguard of research, always seeking to optimize their skills.

The same can be said for mental health practitioners, whose toolkit gets bigger the more we understand the human brain. With so much trauma all around us, there is also the need for therapy. Over the last few years, a whole community of friends, my husband and I left behind in the northeast, people who perform those lucrative, stressful jobs of the future have sought mental health services and been placed on waitlists due to the scarcity of providers. Though not technological in any way, psychology is a major of and for the future, one that will help the rest of us cope with the changes still to come.

Personally, I got exactly what I wanted out of my college career — and an array of information, a ton of self-knowledge, a chance to learn another language, a blank slate and the opportunity to explore subjects that I suspected wouldn’t stick but were fun and inspiring. I could not have done that in Colombia, had I stayed and studied five years of law. The major I chose, comparative literature, was not hugely popular back then, but it had been back when it was the invention of necessity.

A forerunner to liberal arts, comparative literature was born in the 1940s when educated, multilingual Jewish Europeans fled to the U.S. These intellectuals had already been publishing and corresponding with American intellectuals. They were granted teaching positions at universities and after some time they created departments that specialized in reading all types of philosophical and literary texts in their original Latin, Greek, German, French, and English, developing interesting theories of reception as they compared to others. Eventually, the languages changed with the times, as the immigrants who followed came from other places, and by the time I arrived, no one blinked when I declared my languages to be Spanish and Russian.

These days, comparative literature is mentioned by name when the subject of extinguishing majors arises. For the two years during which I contemplated how to get a job in academia, more and more comp lit departments around the country shuttered their doors. The world has changed — the knowledge of classic texts is not one of the attributes employers seek. Immigrants come bringing new skills but those are not necessarily European languages. All things being equal, I would still argue that a major like comparative literature (or art history, or math, or anthropology) may not sound like key careers to lead the resistance, but to me, they are absolutely key.

Learning to be a critical reader taught me to be a critical thinker. I learned to read the depths of a text and translated that skill to help me read the depths of people and situations. The knowledge I acquired from reading and writing about what I read was great; but the knowledge that arises, the new texts that are created when we put two diverse ones together is exponential. Becoming a literary critic taught me flexible thinking and tuned my eye more precisely to appreciate creativity, structure, rhetoric, technique, and beauty. And while I know that we need programmers, engineers, and scientists to take us into our future, none of it is worth doing if we lack the ability to appreciate, understand, and absorb the beauty of the world. The best college majors, the most useful, will always be those that speak to our whole being. Sometimes I wonder if I’d be better off as a lawyer, but mostly I regret nothing.