My courtship with my husband, like our habit of going on journeys together, began during our graduate school years, when shoestring research grant budgets allowed us to go places but not posh ones. Backpacking, shopping for food at markets more than restaurants, and staying at pensiones or short-term sublets of people’s homes (think Airbnb but word-of-mouth) lent to our experience and a sense of authenticity that made us feel as if we had “lived” somewhere, even when we’d only rested there for a few nights. I remember those days fondly, though I recognize how obnoxious the hubris of early adulthood made my reports back home sound more like lectures. In fact, I believe my younger sisters and brother only recently lifted the ban on my use of the word “authentic.” (Thanks, guys).

The thing is, years later and with more humility, I see how a major factor in feeling capable of getting on an airplane alone to visit France before I spoke any French (1993), or agreeing to meet my then boyfriend in St. Petersburg, Russia (2000), where I had (truly) been living and working for nearly two months, to go on to travel to other unknown places — all of this before wifi and smartphones, was the local library.

Libraries are Universities in and of Themselves

The local library was a treasure trove of pre-travel research: where should I go? What will I do when I arrive there? What kind of research can I access that extends beyond the here and now of the local bookstore? Which is the lightest, cheapest travel book I can actually purchase, without any pressure to buy the book or browse quickly (and somewhat furtively) in the café area? And unlike the café, which as a book lover always makes me panicky about the close proximity of hot beverages to pristine copies of the bestseller list, the library offers many books and someone to consult.

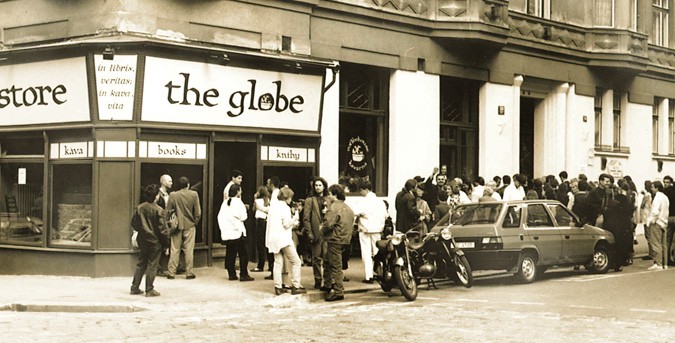

It would be wonderful to think that bookstores and cafés operate the way only a library still does, in which consultation and communal exchange are supported, even if only at whisper-level. In 2000, when J and I stopped in Prague between Moscow and Vienna, the Globe Bookstore offered great coffee, expat (read: vegetarian) food for me, and communal computers on which we could buy minutes to email back with family and friends. Ideal for that quintessential backpacker need of communicating reliably but infrequently with home, the Globe was also the way to fill in the dark spots no travel book would enlighten. There, you could turn to anyone at the next table and say, “where should we go tonight?” or “who’s playing?”

That summer alone we got directions and gave directions, looked up numbers and tapped librarian for advice, figured out next steps and solved problems all around Europe, thanks to local libraries and cafes. Fast forward twenty years, and this is not the situation at the neighborhood Starbucks. It’s simply not. The guy on his AirPods tapping at his keyboard and the book clubs ladies sucking up their lattes through an eco-straw do not give off the most approachable vibes. This is not to fault the big chains, it is a cultural moment. Even at the mom-and-pop coffee place, the cost of the craft tea and oat milk beverage also buys you the right to sit, unaccompanied or otherwise, and not have to commune with those around you.

Bookstores, too, even the most community-building of them, have taken a huge hit from online booksellers. Brick-and-mortar stores have been succumbing to their high rents for nearly a decade. Pause now to consider that in addition to being viable competitors in a digital age in which a storefront will have limited stock, libraries provide a vast catalog, the possibility of ordering what you need, a librarian or archivist who will help you navigate their system and find all of these things. At the local library, all of this is free.

Libraries are Cultural Havens

When was the last time you ask a librarian a question? Next time you’re in Provincetown, Massachusetts, for instance, check out the local P-town library. Doubling as a mini-museum of the area, the library is housed in a restored original building and features a well-equipped children’s area complete with puppet theater and puppets.

The most memorable aspect is the reconstructed, century-old schooner, which due to its size was brought inside in pieces and rebuilt as the centerpiece to the building, its mast visually supporting the height of its three stories like the central pole does the big tent of the circus. The P-town librarians double as curators of the exhibit and other archival materials made available at a special reading room. If you hit them up around lunchtime, librarians transform into tour guides can also point you to the best lobster roll in town and depending on the time of year, invite you to the Moby Dick read-a-thon. This type of location specificity and service to the local community are visible in other public libraries around the country.

At schools and universities we still have these spaces: vibrant exchanges of opinion, reading, researching, debating, and even socializing. Some neighborhoods and towns, like Provincetown or Stockbridge, Massachusetts, both of which have offered my family respite from summer heat waves, or the Coral Gable Public Library, where a professional ballet troupe puts on children’s performances at a nominal fee, also boast these cultural epicenters.

But what about other places, neighborhoods where access to these spaces is not possible (there is not yet a culture of reading and seeking out school and local libraries) or the spaces are not themselves available (libraries are underfunded and understocked)? What good is it to have Miami Dade College host a book fair in downtown Miami every year with world renowned authors, to the communities who haven’t had a chance to develop their taste for reading? This taste is developed early and research shows it is best nurtured through the library model.

The reasons we develop as readers in a library are fairly logical if we stop to think about it. Libraries offer us space that is conducive to sitting down and reading. Unlike purchasing a book, we feel no obligation to pick something up and lumber through it, perhaps causing ourselves an association between reading and negative feelings, such as guilt. Buying something off of Amazon, even with the “look inside” option, will never replace the ability to sit with a book and read a few pages into it, and, without fear of commitment, decide to take it home and give it a whirl. In the worst case scenario, if you don’t finish it, feeling you simply can’t get through it, you return it, the end. Seeing the source of information first hand, too, helps us discern the difference between what is reliable and what is less so. We can trust what’s printed in a book more than we can National Geographic, but online this distinction is not always clear.

Libraries are Forums for Play and Exploration

As a fiction reader, the library formed me with its lack of pressure to finish the book and take a test on it, the experience of checking out a title entirely of my choosing. This is how I emerged into my reading self, in contrast to the battery of assigned books, which, even as an avid reader, I simply didn’t always read. I still remember the smell of my school library, the card catalog (I know, I know), learning to understand the squiggle of letters and numbers that made up the Dewey Decimal code typed onto the white library tape, the sound of the mechanical stamp that like a slug on steroids came down hard on the back slip of paper, leaving behind its slimy trail of due date that I would likely miss and incur fines, payable by my allowance. I could wander around, take my time or rush, take a few books out or none, each of us a master of our library universe. This is why I still love libraries, take my children to them as often as possible, and understand why they are crucial and necessary, especially so now.

Besides browsing, a well-enough stocked library will provide a basic trove of supplementary knowledge and information that even the best of home libraries cannot aspire to provide. I consider myself infinitely fortunate in this realm, having grown up in a home in which two siblings shared a bedroom because the additional one was dedicated to the family “den.” A large, circular work table was surrounded on two sides by bookshelves packed to the gills with my dad’s well-thumbed Russian novels-in-translation and my mom’s classic-tales-everyone-should-read, like Little Women, Jane Austen, and Huckleberry Finn. When we brought home research projects, my father would draw out a surprisingly slim tome entitled Lo Que Tú Debes Saber (What You Should Know). Between the information it contained and my dad’s supplement, it kept the four of us kids sorted well through the eight grade.

But with high school came the need for deeper knowledge and research, and eventually my dad’s book was not enough. Seeing that the Encyclopedia Britannica was the starting point for virtually every topic we were assigned to investigate (yes, kids, Wikipedia was a book before it was a website — and it was peer reviewed!), my parents invested a portion of their travel and leisure fund into this costly, leather bound tomes organized in a row, gold numbers gleaming and setting off my OCD-like need to have every single volume. We were all set.

Until we weren’t, because our library had more sources, more books, more information, more of what we needed. There were periodicals on microfiche, documentaries on video, and even audio recordings I remember listening to on black cassette tapes decks with large handles and an internal serial number identified in white paint marker, that were to be checked out alongside the tapes. Best of all, there were the librarians, who could help us find our way through research when we were lost before we had even started.

The subject of library revitalization is even more important now that 25 years ago, when I was preparing reports on El Salvador, the Byzantine Empire, or Virginia Woolf. A wonderfully thought out, well-researched (of course!) article written by three librarians who have seen the evolution of the library system and its place in society today, divides the public library’s crucial contributions into five categories: community-building, social integrators, low cost art centers, free educators, and champions for the young. Reality is that not everyone is as lucky as I was, learning about the wonders of the library early, equipped with parents who supported the enterprise in both thought and deed.

Libraries as Socio-Political Catalysts

In economically depressed neighborhoods and communities, the local library can revitalize the area in various ways. Housed in buildings that are themselves architecturally important, local libraries also create a flow of traffic and neighboring jobs, a cottage industry in the service of cultural exchange and learning, which is itself fed and nurtured by the resources a local library provides small businesses for free. When library parking lots double as farmer’s markets or craft fairs, as many do a few times a month, or as voting places every couple of years, they show themselves to be crucial to the sustainability of the community and to its democratic process.

The political role of the library doesn’t end there. Topical exhibits on banned books and historical events, and even specialized services for their host communities, such as lunch programs or assistance to the elderly. Some local libraries provide opportunities to perform community service or give clubs and associations a place to meet and resources to better advocate for themselves.

Libraries provide this free opportunity for education to their communities. Just like communities differ from one another in their features and needs, so too, do these services. Places with large immigrant communities will find their local library provides bilingual services as well as ESL classes and opportunities to meet other residents. Libraries also provide resources and support for disabled patrons, members of the LGBTIA community, and people who are underrepresented in other spaces. The question of cost is a big part of the conversation about visibility and access and libraries continue to do all of what they do for free.

Giving people access to art outside of costly museum exhibits, as well as providing hands-on art workshops, local libraries are social equalizers. A library can provide access to renowned and inspirational speakers, film screenings, visual and graphic artists, musical recitals and even dance performances, like the ones I have attended, and it does all of this for no cost or at least for less than the price of a movie. As live performances and museums climb in price, this local and accessible resource, the library, needs to be seen as what it is — priceless.

It is never too young to start our kids on this journey of appreciation of the local library. Anyone who has been a parent to an infant-through-toddler and turned to the local library can vouch it is an oasis from the overheated misery of a meltdown. Quiet, clean, climate-controlled, the library and its well-scheduled story time; row upon row of picture books; small tables that are just right. As kids get older, they engage with all the other aspects of the experience, like the opportunity to exercise choice and the responsibility of caring for and returning what they’ve borrowed. They see the author bios on the wall, they attend a few lectures or performances, they make use of all the resources available and then, one day, they go and vote, hopefully choosing those to power who see the importance of reinvesting in our local library.