Before delving into what we can each do to learn how to dance salsa, I would like to try an experiment. Go ahead and click open another tab. When you reach Google, type the following phrase into the search bar, slowly: “how to dance salsa.” What you will find, as I did, is that right around the time the finger released the “a” key in “dance,” the whole phrase pops up first in line in predictive text, second only to “how to dance.” In other words, we are not alone in our quest to learn how to master — or at the very least, muster — this sultry, musically rigorous and socially complex, highly gyrational artifact of Latino-Caribbean culture.

The first step toward dancing might be to understand it. Salsa is musically and ethnographically layered, a product of migrations and musical encounters. Easily enjoyable to a listener and foot tapper, salsa is notorious for requiring skilled dancers to fully perform its fast-paced, rhythmic demands. In Dirty Dancing, a bildungsroman of the practiced city girl ready for the sultry structure of a ballroom mambo class has to learn to cut loose and relax her hips enough to master the holy grail of dancing: the street-worthy salsa of the nighttime parties with the employees.

For those of us who not only are not Jennifer Grey or the sorely missed, talented icon that is Patrick Swayze, but also happen to be Latino, there is an expectation of mastery, an assumption that the skill is genetic or culturally implanted. While that all may in part be true, managing the steps, the ballroom grace, and the street-worthy looseness, all together at a fast tempo benefits from more learning, hands on instruction, and lots of practice.

Roots of Salsa

Born in the new continent, the kind of salsa your neighbor played at the last block party is a mixture of various regional Latin American musical types together with Afro Caribbean beats and North American forms like jazz and blues. In fact, the term “salsa” itself is newer than the musical forms that now are classified as such, acting as a sort of generic label to describe different popular styles — from mambo to cumbia — resulting in an upbeat musical syncretism.

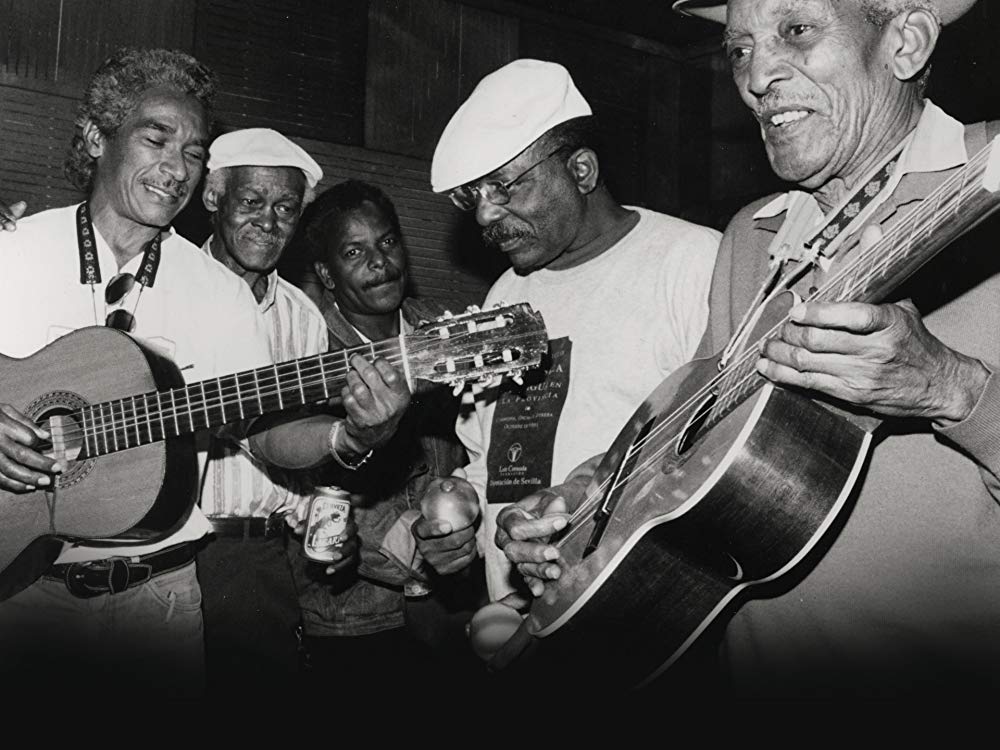

Musically, salsa shares many hallmarks with the Cuban musical form, son. Cuban son predates salsa by a few decades and both are highly percussive, utilizing a vast array of instruments for these purposes: cowbells, maracas, congas, claves, bongos and more. The resemblance between son and older, more distant musical forms is seen clearly in the way the percussive parts are arranged in a the same call-and-response pattern that then breaks into a chorus, much like traditional African music. Those who ascribe the origins of salsa to Cuba are usually thinking of the undeniable Afro-Caribbean flavor of salsa, and they are, at least partly, correct.

Aside from the percussion section, a salsa arrangement features an array of instruments that might seem like an orchestra and a jazz big band had a baby. In fact, the genre features sounds from a variety of instruments, so that it isn’t unusual to have over one dozen musicians in the band. Salsa melodies are carried by the piano, vibraphone, marimba, violin, guitar, flute, and accordion, while a festive brass section features intermittent punctuation from the trumpets, trombones, and saxophones. Even in its array of distinct instruments, salsa’s multicultural origins are clear.

Deconstructing the Elements

I have always imagined that the impressive size of the ensemble and the presence of so many European instruments is the reason why in Spanish, the salsa band is always referred to as an orquesta, a word normally reserved for more highbrow collectives, like chamber music players. These days, even electronic instruments are added for modern effect. So vibrant and lively is the combination of these seemingly disparate instruments coming together, than even the musicians themselves — especially the brass section with their choreographed side-steps — can’t resist the pull of salsa’s common 1-2-3, 1-2 beat. If you are ever in a situation in which a live orquesta is playing salsa, watching the musicians and trying to copy what they are doing is a good primer for trying to nail the steps.

More often than from a live band, salsa music plays from speakers at parties, as background to Latino advertisements on television, and out open windows throughout the neighborhood in the warmer months. If you are Latino, chances are your grandparents might know similar music by a different name, including son, chachacha, mambo, and guaracha. If you were to ask them to teach you how to dance these styles, you would likely learn a similar step to the basic salsa one, many of the same turns and tricks, but at a slower tempo, which for a beginner is not necessarily a bad thing. An added benefit to learning to dance son or mambo, is that dance partners tend to hold one another a little closer than with faster paced salsa, so if you have a great partner and allow her or him to lead, it’s a bit easier to wing it.

Salsa as we know it today is faster, more complex, a mosaic of cultures and genres. Its much-contested birth was not a static, sedentary thing but rather the result of the emigration of Latino musicians to the United States. Giants like Xavier Cugat first introduced American audiences to Latin musical styles in the 1940s. Israel “Cachao” Lopez first brought mambo to New York from Cuba in the 1950s and his compatriot Mario Bauzá helped it spread like wildfire. Together with Machito, Bauzá took a page from Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, to the effect of producing mambo arrangements that mimicked Big Band style, giving birth to what is called Latin jazz.

As all of these styles continue to evolve in New York city, Puerto Rican musicians like Ray Barretto with his Latin jazz and boogaloo, the two legendary Titos — Puente and Rodriguez — and Héctor Lavoe, each bring in their own stylings, tossing them into the mix. Puerto Rico also brought and its admixture of Afro Caribbean culture, the socio-political lyrics and its presence at the right moment in New York, made this island the other great originator of the style of music we now call salsa.

If Cuban son and mambo had not made it to New York in the 1950s, where they dropped into a giant cauldron of musicians hailing from Puerto Rico, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Panamá, mixed with the vanguard jazz stylings of the American bee-boppers, and gotten stirred up with the red-hot spoon of the music scene of the times, today we would have son, guaracha, boogaloo, mambo, merengue, but no salsa. Salsa, then, was born in New York, the creolized offspring of new immigrant music from Latin America, the poster child for the cultural revolution that was happening in that space at that moment.

By the 1960s, salsa was being called salsa, lighting up the nightclubs in New York City and all the rage. Its name, as any good eater of Latin food know, means “sauce”, and while the reasons for its adoption as a name are not clear, some suspect it originated when lively performers would shout it into the crowd to rev them up more, just as the queen of salsa Celia Cruz would take to exclaiming “azúcar!” to the same effect. By now, the popularity of salsa was enough to inspire a Motown-like production effort that gathered the greatest names in the business under their own label: the Fania All-Stars.

Judy Morales/Fania Records

The brainchild of Dominican bandleader Johnny Pacheco and American attorney Jerry Massucci, Fania All-Stars produced New York City salsa records for Latinos from all around, including Puerto Rican Hector Lavoe, Cubana extraordinaire Celia Cruz, Nicaraguan Willie Colón, Panamanian Ruben Blades, and American Ray Barretto. This is another great attribute of salsa. As an umbrella term, it reunites the aesthetic beauty of the form with its popular and progressive thrust, but it also unites the community together under the same Latinidad of our experience. Salsa blurs the boundaries between one distinct Latino culture and another a little, perhaps just enough to bring us closer together.

Of Course, There are Always Dissenters

Tito Puente, the virtuoso percussionist and bandleader, champion of mambo and Latin jazz, famously objected to the name, reinforcing his identity as a musician, not a cook. Having had the privilege of seeing him live in concert toward the beginning of my college career and toward the end of his, in a now unbelievably intimate and wonderful venue on campus, I can imagine the reason for his objection. Puente led that orquesta the way any classical conductor would theirs, same poise but more warmth and flavor. Perhaps he imagined that in others’ hands, a generalized and popularized idea like salsa might demean the form.

Enhanced it with more regional flavor is what it has done, this oozing and spreading of salsa a genre of dance and music. Now, you can find distinct styles of salsa in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Dominican Republic, and even New York and Miami. Certainly, if you don’t live in these cities or even if you do and you’re too shy to go to the local salsa joint, take down a couple of mojitos for courage, and allow yourself to be taken out to the dance floor, there are things you can do to learn to dance salsa.

So, How Can You Learn to Salsa?

While I’m sure it does not need any endorsement from me, the comfort and value of taking unlimited instruction in the privacy of your home via a streaming service, YouTube or a NintendoWii-type console cannot be oversold. With or without a partner, it’s you against you in front of the screen, and if a foot is stepped on in the living room with no one there to hear it, was it stepped on at all? The drawbacks of solitary auto-didacticism is that in this case it takes an essentially social activity and turns it into a lonesome occupation. Without company or accountability, it’s easy to get stuck.

On the other hand, you can always learn with or from a friend. While the latter is ideal and most cost effective, the former also works. Call around dance school near you and inquire whether they offer it. Most places will tell you that there is no need to have your own partner, though if you do they will also accommodate that, too. Having a hands-on instructor to demonstrate, lead, and correct can encourage a more rapid evolution of your dancing skills. The social and jovial ambience of adult dance instruction that makes it a popular pastime of the retired set is precisely the lighthearted optimism that our working lives often need. It’s a great way to make new friends and bond with older ones.

Like with kicking a bad habit, salsa is best learned with together with or from a friend. Or better yet, like learning a language through total immersion, it might be ideally suited for learning with or from a lover. Unlike taking up a different hobby that requires equipment or special space and time set aside, dancing is a spontaneously occurring phenomenon that comes up at social gatherings. Amongst us Latinos, salsa dancing comes up quite a lot. In fact, the single-most surprising aspect of parties (keg parties and the like) that I encountered on arrival in the United States was the lack of dancing and even music.

At home in Colombia, no party is complete without dancing. There are definitely breaks for drinking, eating, and even standing around chatting, but the majority of the time is spent dancing. Popular styles include easier-to-master merengues and vallenatos, but salsa is a mainstay.

Since arriving in the U.S. and dropping into the pan-Latino community, I have noticed that most people from Central America, the Caribbean, and the Andean region identify with salsa. This effect certainly fades as we go deeper into the Southern Cone countries, but if you show up at a quinceañera or a wedding, don’t be surprised if the speakers blare some Buena Vista Social Club while guests pair up and spin off onto the dance floor. At a certain point, no amount of lessons or practice amounts to a hill of beans if we aren’t ready to be like Baby, grab that watermelon and show up to the after-hours party. If we’re lucky someone as dreamy to us a Johnny will agree to practice the steps as many times as needed.