The month of July in the United States is like one of those bomb popsicles from the ice cream truck — all red, white, and blue, a sticky-sweet convergence of summer and our nation’s independence from England. Barbecues and picnic celebrations abound, and fireworks are traditionally a big part of the festivities, to the dismay of startled young children and the terrified dogs of the United States. Unlike the commemorative parades and solemn silences of Memorial Day and Veteran’s Day observations, the 4th of July is all about making the most of summer and enjoying some of the freedoms many people gained in 1776. It’s also an excellent time to reflect on the many freedoms still not uniformly afforded to everyone in our country.

Each year, when July 4th comes around, I am reminded that we are celebrating more than just the consolidation of thirteen colonies into a sovereign nation, more than just the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The colonies’ separation from England was not only the inspiration for the French Revolution (1789) against their corrupt monarchy, it was also the spark that set off a wave of independence throughout the American continent. Haiti, taking advantage of Napoleon’s distraction during his expansionist campaigns through Europe, broke free in 1804. Spain’s colonies would follow suit, one by one, beginning with my homeland, Colombia.

Colombia’s Guajira peninsula is the northernmost point on the South American continent. As the Caribbean Sea enrobes the peninsula, a small finger of land called Cabo de la Vela, reaches out beyond the coastline, and it was there that Columbus’s colleague, Alonso de Ojeda, landed in 1499. In typical colonial style, Ojeda claimed the territory for the Spanish crown and prepared a path for the hundreds of Spaniards that would follow, in search of land, power, and the mythical gold of El Dorado. A few rushed settlements were cobbled together in support of this mission to exploit the natural resources of this rich land, until the first proper city, Santa Marta, was founded in 1525, making it the oldest one on the continent.

Just like in the rest of the “New World,” there were already people living along the Caribbean coast of Colombia, for whom the only new thing was these European men who brought with them weapons and a grab bag of diseases against which they had no immunity. These native tribes, specifically the Tayronas and Quimbayas who lived in Guajira and the base of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, were fearsome warriors and resisted the Spanish colonizers as long as they could. They were able to stave off the full brunt of colonization for about 50 years, but by the middle of the 17th century, Spain firmly held the reins. Now it was time to work the land and send the resources back to Europe.

The practice originated by Rodrigo de Bastidas, founder of Santa Marta, to exterminate all of the indigenous people he encountered, inspired the conquistadores who came after to follow suit. When this genocidal practice left the colonizers without a labor force, one of the most prominent emissaries of the Crown, Bartolomé de las Casas, introduced the idea of bringing over African people to be sold as slaves. The Spanish Crown not only rolled with the idea, but they turned Cartagena de Indias, founded in 1530 by Pedro de Heredia, into the central slave market for the whole continent.

It’s location on the Caribbean coast, just south of Santa Marta, had already made Cartagena the center of trade for the growing colonies and the island of Barú, just off its coast, served as a quarantine and inspection station for the newly arrived African men, women, and children, in preparation for their sale. Landowners all the way from present-day Perú up through Costa Rica traveled to Cartagena to purchase their slaves. Eventually, the slave trade became Spain’s biggest moneymaker, even more, lucrative than sugarcane and all of the gold they mined, and Colombia was at the center of this nefarious business.

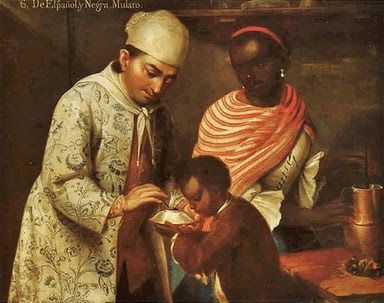

This shameful enterprise, in which far more humans were trafficked than to North America, lasted 350 years, leaving Colombia with the third largest black population outside of Africa, second only to Brazil in South America. By the time President José Hilario López outlawed slavery in Colombia in 1840, using the national coffer to purchase the freedom of those who hadn’t been able to do it for themselves, black slaves had worked the land, built infrastructure, done domestic work, served in the military during the civil war that ensued after independence, enriched the culture in infinite ways, but landed at the bottom of a perversely color-coded caste system.

During the three centuries of colonial rule, Spain maintained its grip on the rich land of South America through a remote ruling system called the encomienda. A creole feudalism, the encomienda relied on locally assigned virreyes or viceroys, sent from Spain to keep control over the population and ensure that the Crown’s interests were protected. Governing over such a vast land, these European emissaries all dreamt of returning home laden with treasures and carried out the bidding of the King by force and the most efficient tool for mass indoctrination — religion. Catholic conversions were imposed on all and the Church became practically a branch of government, attributing the poor treatment of the lower castes, much like in India, to the will of the Divine.

Despite the conquistadores’ best efforts, a fraction of the indigenous population remained in La Nueva Granada (the name given to Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama), many of them intermarrying with American-born whites. Their offspring, labeled mestizos, were held in higher esteem than full-blooded Native Americans, mulatos (descended from whites and blacks), or zambos (descended from blacks and aboriginal peoples). At the bottom of the totem pole were the African slaves and at the very top were the criollos or American-born whites descended from Spaniards. I remember charting the stratification in clase de historia in seventh grade, using colored pencils to enhance my memorization of the terms, and realizing that the whole social structure looked more like an art class exercise in hue and tone than anything having to do with people.

The criollos were the encomenderos, the feudal lords who answered to the virreyes and whose job was to ensure that the labor force did their work. In return, they were supposed to take care of the mestizos, mulatos, and mambos who worked for them, but they kept the bulk of the profits. Pay for the grueling physical work was mainly room and board plus a small stipend, which in some cases, allowed a slave to purchase his or her own freedom. The criollo class enjoyed the privilege of being the bosses and accruing wealth and land. They were educated, sometimes in Europe, and so they comprised the elite class of the colonies. But unlike their Spanish counterparts, criollos had no political power.

Imbuing this class of people with money and land but no power was the South American version of taxation without representation, a recipe for disaster for the Crown. Wealthy but disenfranchised, powerful but not enough, the criollos were the biggest supporters of the revolutionary thrust, as early as 1783. Colombia’s very own Alexander Hamilton, Mr. Antonio Nariño, was one such criollo, who after studying in France came back to what was called La Nueva Granada and drafted La declaración de los derechos del hombre. He published this document in 1784, amassing support from others who would grow to be prominent figures, like Simón Bolivar, who will eventually be the first president of La Gran Colombia.

These ambitious criollos, ready to govern themselves, were instrumental in organizing the mestizos, mulatos, and campesinos, educating them on what was possible and strategizing their approach. In the meantime, Napoleon had invaded Spain in 1808, removing Ferdinand VII from power. All of this preparation fed a perfect storm on July 20, 1810, when at a public function in Santa Fe’s (as Bogotá was known then) central square, a Spanish official refused to lend the criollos a flower vase they had requested to borrow for a welcome ceremony to honor a visiting commissioner. This seemingly inconsequential denial began as an argument between the ruling class and the highest class. It resulted in an armed conflict between Spaniards and criollos, which the latter won.

The date of this spontaneous battle is sealed in our collective memory as the day we declared independence from Spain, especially because Spain was disabled from putting up much resistance at the time. Many of our country’s important documents and historical records are kept in one of the last remaining structures from around the time of this cry for independence, called La casa del florero, after this most useful vase. The actual house is built in a style that evokes the various cultural components that contributed to the architectural style of the time, including features that were typical for the Arab communities who settled in Barranquilla and Cartagena.

We celebrate our independence every July 20th, though historically, this date marked only our emancipation from Spain. The six years that ensued, nicknamed La patria boba, by Nariño, was a period of civil unrest and clashes between two separate camps: Nariño’s centralists and Camilo Torres Tenorio’s federalists. Though this one didn’t end in a duel, it is a story reminiscent of the birth of the United States, too, with Hamilton and Burr, Washington and Jefferson, holding opposing views on how to proceed. The chaos of 1810-1816 prevented the Americans from realizing the imminent threat that Spain presented once more, as Napoleon was defeated and Ferdinand VII reinstated.

Watching the Americans flounder to set up their government, the Spanish Crown plotted to take over again, through their Reconquista efforts, sending Pablo Morillo to Cartagena to “pacify” the Americans. Picture it! It’s as if King George had set out to try to take over the United States again after 1776. Having to continue fighting the Spaniards in a series of memorable battles detracted from officially organizing the Colombian government. Additionally, the criollo forces who fought for independence hailed from a wider region than just present-day Colombia. The area, which comprised the present-day Venezuela, Panamá, Ecuador, and Colombia, proved to be too unwieldy and full of far too many dissenting ideas to remain as one. Tensions between the various peoples governed under that title, for instance the Venezuelans frustration when Bolívar, himself born in Caracas, picked Bogotá as the capital instead. Beginning in 1820 and completed by the end of the decade, Colombia (still inclusive of Panamá at that point) became a nation unto itself.

Today, our forefathers from the various corners of La Gran Colombia are represented on our currency, memorialized in our history books and museums. Some brave criollo women, like Policarpa Salavarrieta, who was executed by the Spaniards for helping in the movement, are also remembered. The process of fully becoming a nation only began on July 20, 1810. The tri-color flag — half yellow to represent the stolen gold, a quarter blue to represent the Atlantic and Pacific coastlines we are blessed with, a quarter red in memory of the spilled blood of our war heroes, our indigenous peoples, our emancipated slaves — followed in 1851. Our anthem, all 24 verses of it, is considered the second most beautiful in the world after France’s La Marselleise, was written in 1920. Finally, the national shield (which does not appear on the flag, distinguishing it from Ecuador and Venezuela who use the same yellow, blue, and red plus their own national shields), came in 1955, finally endowing us will all of the trappings of a free country.

Spanish is still the official language of Colombia and Catholicism its official religion, though freedom of religion, speech, and culture are rights enshrined since our original constitution, thanks to Nariño. In 1992, a brand new constitution dissolved the link between Church and State, finally doing away with some of the more primitive restrictions that remained, like the one against divorce.

Today, Colombia has nearly 50 million citizens throughout the country. Despite other civil problems, it has maintained a nearly uninterrupted centralized democracy, an unusual condition in Latin America. Though no longer pristine, the diverse landscapes and climates make for a varied agricultural products, different regional personalities, and countless amazing vacation spots. July, for me, will always be the month of independence, enlightenment, and the belief that together we can rise against our oppressors, and win.

For Image credit or remove please email for immediate removal - info@belatina.com