Updated 2/27/2020 to reflect the news that Dr. Matthews’ employer is actively formulating a vaccine against the coronavirus with the U.S. Health and Human Services Department.

For a century, the United States has turned its focus to particular groups within our population, honoring them for a day, a week, and up to a month. Veterans’ Day is perhaps the first example, dating back to late 1919 when it began as a celebration of Armistice Day at the end of World War I. This was a first effort to shine the spotlight on war heroes in recognition of their service.

By the 1920s, the practice of designating a date to pay tribute to a specific demographic was a way of paying tribute to the contributions of minority populations that continued to be marginalized in society. The work of inclusion, recognition, and even reparation was attempted by these weeks, widening the dominant paradigm and narrative to allow for those formerly erased.

For example, historian Carter G. Woodson inaugurated what he called “Negro History Week” in 1926, in an attempt to incorporate the African-American experience into the master narrative of American history. A week in February was chosen, coinciding with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln, the president who outlawed slavery, and Frederick Douglass, who escaped the cruel and unusual institution to spend the rest of his life fighting for freedom.

Emerging 50 years after Emancipation and 50 before the abolition of Jim Crow laws, by the 1970s, the week would become a month — Black History Month — dedicated, to paraphrase President Ford, to rectify the gross omission of the vast contributions of African Americans to the nation. Just as the purpose of February’s designation is to recognize Black Americans, other marginalized demographics have also found a place on the calendar to call their own: National Hispanic Heritage Month (September), Asian Pacific American Heritage Month (May), Women’s History Month (March).

By the same logic, the fact that on February 11th we observe the International Day of Women and Girls in Science is proof that the role we play in STEM was in dire need of some attention across the world. Historically, the presence of women in science-related fields has been one of those absurd taboos in cultures around the world, as traditional gender roles have played into keeping women tied to domesticity and absent from spaces of inquiry, like laboratories.

One would think that the smattering of prominent female scientists, those who managed to upturn these ossified conventions of the 20th century (chemists like Marie Curie, engineers like Amelia Earhart, astrophysicists like Katherine Johnson), would have sufficiently proven the exception to the rule theory, but no. Instead, it took a resolution passed by the United Nations in 2016 to highlight that the 21st century will require more of us as a species. It will be so much, in fact, that we will no longer have the luxury to squander the talents of more than half our global population by keeping women out of STEM.

This day of celebration and recognition is a step in promoting gender equality and the advancement of science and infrastructure, in the hopes of increasing egalitarianism by 2030. At the moment, while women make up right around 51% of the world’s population, only 30% of researchers across the world are women. The statistics around the number of women who pursue STEM careers and work in manufacturing, construction, engineering, and related fields are even more disproportionately low. Clearly, we still need at least one day a year to shine a light onto all of our smart-at-STEM women and girls.

Here at BELatina, we didn’t have to look much further than our backyard to find a remarkable member of the STEM community. Just as we are blessed to be surrounded by Latina artists, educators, and entrepreneurs in our communities, we can also find surgeons, architects, and, in this case, specialized researchers, working daily to use their knowledge and expertise for the public good. Highlighting the contributions of one of these women is our celebration of International Day of Women and Girls in Science, a spotlight on one Latina who has helped lay down a path for others to follow.

Miguelina Matthews was born and raised in Manhattan, surrounded by a large extended family. Latina might be too general a label for this scientist who now works for a pharmaceutical company. More precisely, Dr. Matthews refers to herself as a Jewminican, half Dominican (on mom’s side), half Ashkenazi Jewish (on dad’s), fully identifying with both of her families’ cultures.

Dr. Matthews grew up with her Spanish-speaking tías and grandmother, as well as her father’s English-speaking family, comfortably switching between the two. Her proximity to both languages and the fact that her father didn’t learn Spanish (“Until recently,” she chuckled, noting that all of a sudden, he seems to have a much greater command and comprehension than she remembered) firmly established her bilingualism. Spanish, though spoken domestically only, took sufficient root enough in her that she doubled up on majors, pursuing both a pre-med curriculum and a B.A. in Spanish literature.

During her early years, attending a girls-only elementary school in Manhattan, Dr. Matthews was keenly aware of her languages and cultures at home. She felt then, and does still now, fully of her mother’s family and fully of her Bronx-born, Jewish family. The aspects of her hybridity refreshingly coexist without conflict, and I begin to ascribe her ease and self-awareness to New York City’s signature multiculturalism. But Dr. Matthews, who I have been calling by her familiar nickname, Migi, quicker disabuses me of that notion.

“None of the people in my elementary school looked like me,” she assures me, noting that her cohort was largely Jewish but no one she knew spoke Spanish like her mother and their family. I take a moment to process this — as a Jew growing up in Latin America, my Jewish-ness is what set me apart.

I ask Migi how this played out in effect, this homogeneity at her school, thinking about both her and my experience as Bizarro-versions of each other. “I vaguely remember feeling that I should…and I don’t know if someone actually said it or if I just felt as if I should but…I thought I needed to straighten my hair.”

“Same!” I exclaim, carried away, and quickly try to bring it back to her but she seems as piqued by this mirror as I am.” Do you straighten it now?” I ask, clarifying that I don’t bother, living in a humid climate.

“No, not really,” she said, and we both leave the rest unsaid, though I’m confident we are both long past the point of feeling the pressure to pass.

But as girls in grade school, identity is still raw, more a vulnerability than an asset. Standing out from the crowd can be difficult. Anecdotally, I have never felt more Jewish than when I lived in Colombia, where I was very much in the minority. I imagine Migi’s Latinidad may have been a tricky wave to surf at a small, culturally uniform, unisex school, but difference is also a strong galvanizing force. She acknowledges the great gift her family gave her by sending her to private school, noting that though she felt different from everyone else, she found ways to navigate. In fact, Dr. Matthews acknowledges, she was happy to move onto a more diverse high school, one which, at the very least, also included boys.

We must be exact contemporaries, Migi and I, I thought when her name jumped off the page of my monthly assignment sheet. As my mental Rolodex whirred through a couple of decades, it settled on my first years in the U.S., when I arrived for college. I couldn’t call up a face but felt as if this name — Miguelina Matthews — its simultaneous here-ness and there-ness, was one I had read on an attendance list or a program.

Indeed, when I ask Migi if she went to Cornell for undergrad, she quickly confirms that we overlapped exactly. Given her diverse interests in both the arts and the sciences, it is quite likely that we sat in the same class at least once. “I’m definitely a face person, I’m sure if I saw you, I would remember you,” she notes graciously and I laugh because now I know I must have seen her name written out — I’m definitely more of a name person.

Being at the same college during the same part of the decade, both of us GenXers, we might have both been sitting in the same Spanish literature class right around the time the word “Hispanic” was being replaced by “Latino.” Due to our peculiar background, however, me being Latin American (not Latina) and she being raised in Manhattan, where individualism is prized as a personality trait, we were in some ways spared the politics of this particular issue. Instead, after years of serving as representatives of our minority cultures, we were both released to a school with over 20,000 students, a place where diversity thrives as the inevitable result of the numbers game.

“How did you like going to such a big and diverse school,” I ask her, thinking of the relief I felt when I left behind my years of moving through each grade with the same batch of 80 people. Nothing about the class size at Cornell was intimidating to Dr. Matthews when she went there, in part, she says, because her father is an alumnus and she’d had the opportunity to visit the campus and become familiar with its breadth.

Instead, she remembers those years as being full of intense self-learning. Dr. Matthews went to college convinced that she would become a medical doctor. Unlike many freshmen, she started out with complete conviction, having always had a focused interest in biological sciences. She realized pretty quickly, mainly through following the prescribed pre-med curriculum, that her happy place was the lab, not the library. Losing momentum in her path toward pursuing an M.D., Migi ended up taking her degree in literature and leaving one or two classes in her biology major undone, graduating early but a few credits short of completing that second degree.

Though she was put off from pursuing a medical degree, Dr. Matthew’s mentorship under Professor Elaine Tolson at the Vet School inspired her to stay in Ithaca for an extra semester. Though she had taken her degree, she wanted to stay and live the last few months of college life with her friends, sure, but the work she was doing up with Professor Tolson inspired her: research on Lyme disease. Her work in the lab even propelled her to finish all of the coursework she had left undone — classes in epidemiology and microbiology (also taught by inspiring female professors) — and develop a passion for studying infectious disease.

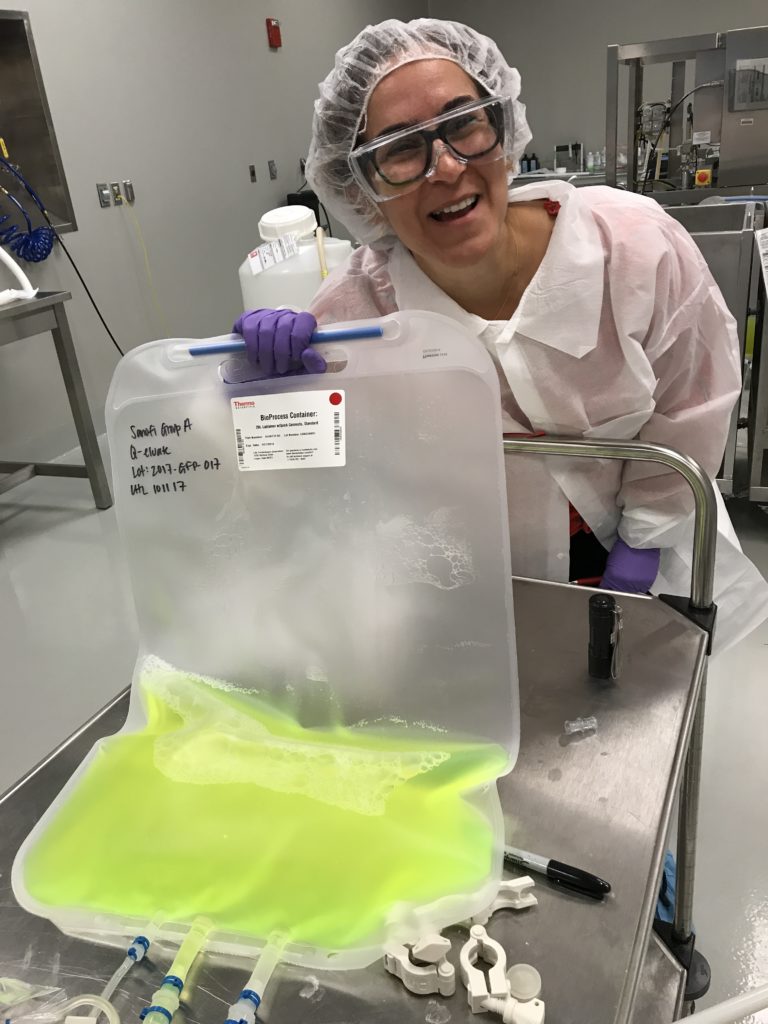

After getting that first degree, Dr. Matthews enrolled at SUNY Stonybrook, one of the leading programs on infectious disease at the time. Her degree program required her to rotate through various labs for a year, searching for the right fit and committing to a single lab that focuses on a particular set of diseases. She did this very thing, only to find herself in a predicament: a year after joining the lab, the professor that ran it moved to Yale University, essentially to inaugurate their infectious disease lab. Migi moved with him, loading up everything from vials and cultures to tanks of liquid nitrogen into the back of the truck and helping to drive the entire operation from Stonybrook to New Haven, she reminisces. (Today, Yale boasts one of the leading labs in the country, a direct result of this move).

At Yale, Migi became Dr. Matthews, not a medical doctor as she once imagined she would be, but a PhD in infectious diseases, with a specialty in pneumonia and similar viruses. “That reminds me,” I interrupt. “This doesn’t have to do with women in STEM but what do you think about the coronavirus?” I ask, feeling somewhat embarrassed about my question.

But then I’m suddenly so glad I did, as Dr. Matthews is reminded of a story that makes me both cringe and laugh at once, empathizing with the discomfort she must have felt at the time. Evidently, she defended her dissertation in 2003, right around when the SARS outbreak had the whole world worried as we are now. Once she finished her presentation, she realized in horror that her father, invited to bear witness to her defense, had raised his hand to ask a question. Tentatively, Migi calls on him and he asks: “What does your research have to do with SARS?”, essentially asking her to solve the global conundrum or at least think fast to come up with a good response. She must have done just that because she passed her defense, but the stress of the moment has erased her memory of what exactly that was.

Remembering her words calmed me, but not nearly as much as the message I got from her a few days ago, weeks after my profile on her was originally published, telling me what she could not reveal during our prior conversation. Researchers are indeed on the brink of being able to produce something perhaps even better than a cure: a vaccine against the coronavirus. And if you thought Migi Matthews could not possibly get any cooler, her response to my emoji-laden message back was: “…and the vaccine is being developed right here in NY.”

After obtaining her doctorate, Migi was expected to take on one post-doctoral position after the next, a convention of her field. These low-paying, high-output positions were not at all what she had in mind. She realized soon after graduation that she would have to jump through the right hoops in order to eventually land an academic position running her own lab and decided this wasn’t a good fit for her. “Yale,” she reflects, “did a poor job preparing us for any job outside academia. And I didn’t want to be post-doc forever. And I didn’t want to move too far from my family in NYC.” From my vantage point in the humanities, I had a similar experience.

“So what did you do,” I ask her. “How did you get out?” Migi told me about attending a job fair in New York just after she took her doctoral degree. She was offered a position at a molecular biology company, asked to create a diagnostic. She took the job and never looked back. “Were your friends in academia supportive,” I ask, and I can practically see her shaking her head no.

“They thought I was a sell-out, at first,” she says, noting that it was rare at the time not to follow the academic path. Evidently today, these non-academic jobs are less rare. Did they come around? I desperately want to know. “Eventually, yes,” she says. “Some of them did.”

One of Dr. Matthew’s favorite jobs was in vaccine manufacturing. She felt fulfilled by following her viruses full circle — from understanding them, to curing them, to preventing them. An expert in pneumonia and similar diseases, that position was practically custom made. She has worked in research and development positions, manufacturing, and now in high-detail global quality control. Traveling around the world to places that produce both injectable and tablet-form medications, Miguelina Matthews makes sure that these various labs are doing their job correctly.

Over the last 17 years, Dr. Matthews has had her fair share of job environments and managers. We talk about the great bosses she’s had, noting that many, though not all, have been women. More than their gender, she reflects on the qualities of a good boss: Someone who gives positive reinforcement, support, and credit when it’s due. She cites listening as the most crucial skill and micromanaging as the most destructive to her work. In previous positions, she, too, had managed people, and though she doesn’t mind doing it, she prefers to work on her own.

“Has this all been more difficult for you being a woman?” I ask. Dr. Matthews doesn’t exactly say yes. She agrees that she once had a rude awakening when she realized that a male counterpart grossly out-earned her despite having lesser qualifications. I practically gasped. “How did you rectify the situation?”

“I reported it to my boss, who was a woman, and she advocated for me and got me the same amount,” she said. “Now, I know how to advocate for myself and I always advise women never to take the first offer. Always negotiate, even if it’s just the intangibles, things like vacation time.”

Not one to over-dramatize, Dr. Matthews cites a single incidence in which she has felt discriminated against at work. As a single woman without dependents, she is asked to travel a lot more than her counterparts who have partners or kids, regardless of gender. She both understands the rationale but is understandably irritated by the discrepancy. I murmur my assent and empathy.

“So being a Latina in your field? Is it a positive? A superpower?” I ask.

Dr. Matthews laughs a little. “I don’t know,” she says, and I get the feeling that she is consummately empirical, made uncomfortable by assumptions and generalizations. She changes the subject, suddenly remembering that I told her I’m Colombian. “I’m actually supposed to be in Colombia in March,” she says. “I’ll be in Bogotá for work, so I extended my trip for a week and will visit Medellín and Cartagena.”

“You will have such a great time,” I assure her. “You chose great cities to visit; can I send you a couple of recommendations?” I ask.

“Please do,” she says. “It’s my first trip to Colombia.” And that’s when I realized that her Latina identity might not have made Dr. Matthews who she is, but it certainly colors how she sees the world, both inside the lab and out.

For Image credit or remove please email for immediate removal - info@belatina.com