The next time you feel yourself growing impatient with a selfie photo-shoot or feel that taking elaborate pains to photograph oneself is the work of vanity (am I projecting?), remind yourself that the very first female selfies were a revolutionary act. Self-portraiture became a trend during the Renaissance, long before the invention of the automatic camera. The original selfies were paintings, sketches, and occasionally sculptures, but their effect was similar. In a self-portrait, like in a selfie, the artist has control over the representation and style of the figure. Becoming the gazer as well as the object of that gaze was a novel and transgressive process for women.

Initially, artists were not particularly fond of self-portraits. Sometimes, they might include a shrunken avatar of themselves within the frame, a miniature witness to the scene they were depicting. Self-portraiture was introduced by Albrecht Dürer in the 15th century when he became fixated on painting his own face and torso. Dürer’s work inspired a whole genre, and many other artists went on to contribute their own self-portraits, perhaps most famously of all the Dutch master Rembrandt, followed closely by his latter-day compatriot, Vincent Van Gogh.

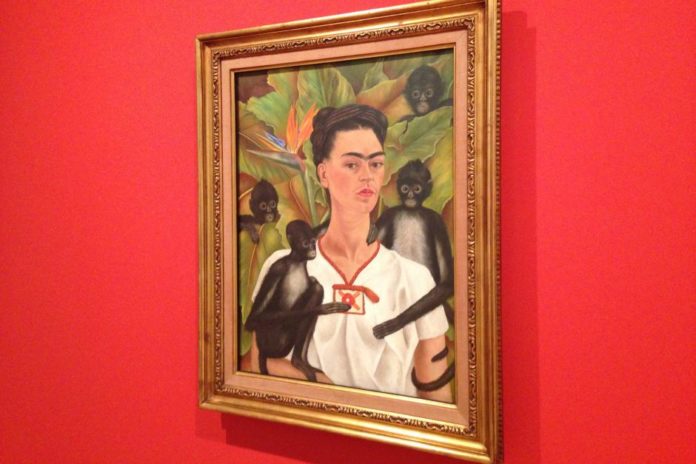

Personally, the idea of a self-portrait immediately returns to me the mental image of pale-faced Rembrandt against an impossibly black background; of ginger-haired Van Gogh awash in painterly swirls; of strong-browed Frida Kahlo in her colorful dress. But if you were to look at a catalog of European Renaissance art once self-portraits started trending, you will find no Kahlos: the faces looking back at you would be overwhelmingly male. Female artists in the Renaissance had work to do to pave the way so that centuries later a woman’s painting of herself would be considered important, rather than merely decorative.

The resistance of the art world to the female self-portrait was rooted in the general idea that women were not worthy of being taken seriously as artists. Deprived of the possibility of acquiring fame and renown through art, a female artist’s selfie would not typically command the sort of attention or wall space as that of a well-respected male. Sadly, women were the ones who had a real need to dabble in selfies, since in the 17th century, female artists were prohibited from taking life-drawing classes. Without live models to sketch, where could women turn but to the mirror?

The First Selfies Were Self Portraits

Sofonisba Anguissola, the Italian Renaissance painter did just that. Her 1556 Self-Portrait at the Easel Painting a Devotional Panel shows the artist dressed modestly, working on a canvas that depicts the Madonna and Child. Anguissola’s decision to juxtapose the Virgin Mary and her own form, encourages the viewer to perceive equivalent virtue in both figures. The artist also takes pains to include her palette, brushes, and even her mahlstick (the original selfie stick, used to support the artist’s tiring arm as she paints), in an effort to thematize the skill and craft of the artist, to foreground greater visibility for female artists like herself, who were generally considered less-than-real artists, creators of decorative pieces. Her attempt to be taken seriously is punctuated by her biggest power move: gazing back directly at the viewer.

Something about the way that Anguissola reaches beyond the frame, engaging with the viewer rather than with her canvas is reminiscent of Velázquez confidently gazing at the audience, rather than at his model or his easel, in the famous Las Meninas. But Velázquez was not painting a self-portrait; instead, he was the court painter for the Spanish crown, commissioned to produce a series of portraits of la infanta Margarita. The decision to place himself at the center of a painting designed for monarchs, demonstrates a confidence that only a male painter could have at that time. Anguissola’s self-portrait, its very existence already a rarity, borders on the revolutionary as she demurely breaks the conventions of bourgeois etiquette and returns the gaze.

Meanwhile, self-portraits continued to be all the rage throughout the humanist revival of Europe’s Renaissance. Women, eager to be taken seriously in their devotion and talent, were excited by the genre, noticing that including the artist’s own countenance on the canvas seemed to increase their visibility and good repute. Men had no issue marketing their art in this manner. Since they already had access to the salons, associating their names with their faces only increased the interest the public had in the art, as well as creating a sort of cult of personality.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s film North by Northwest (1959), there is a sequence in which when the villains pursue Cary Grant’s character as he takes a shortcut through a woman’s hotel room, startling her. Initially shocked by his rapidly retreating body, the woman’s mood quickly shifts when the intruder turns and she sees Grant’s face. This meta-cinematic moment confuses the internal reality of the film, in which Grant is an anonymous person being chased, and the external reality, in which he is a Hollywood star. Grant is, in that moment, both his character and himself as the lady he barges in on swoons instead of screaming. Similarly, self-portraits by famous artists blur the line between their sheer artistic value and their role as an artist’s selfie, a business card or advertisement for his fans.

Female artists, too, wanted to get their names and work out there, and self-portraiture offered them a unique opportunity to attempt a way around the social norms requiring women to remain out of the spotlight. Another Italian Renaissance artist, Artemisia Gentileschi, paints herself circa 1638, and rather than showing us her tools or revealing the subject of the canvas on her easel, she chooses to present herself as an allegory of painting itself. Borrowing a symbol from Cesare Ripa’s book on iconography, a gold chain she wears in the painting, elevates her to an archetypal-type figure, allowing Gentileschi to skirt criticism for the un-ladylike move of putting her image out there. And while Gentileschi refrains from showing us her work, she shows herself at work, her body contorted into a position that illustrates the great physical demands on the painter, ones that she is capable of meeting.

By the 18th century, women artists had managed to jam a toe in the door. Salons were more open to hanging art made by a few women and self-portraiture continued to be a window into the evolution of gender in the art world. One of the female artists who was invited to exhibit was French painter Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, whose Self-Portrait with Two Pupils (1785) shows the artist dressed in an elegant gown and hat, flanked by two junior colleagues who are also elegantly attired. Her canvas is not visible to us, but we are led to believe she is in the process of painting her self-portrait — hence the outfit.

Unlike Gentileschi, who presents a public version of herself that trades propriety and etiquette for a clear sign of her hard work and enterprise, Labille-Guiard foregrounds the contradictions inherent in being a female artist. The artist’s feminine attire and ladylike posture are presented together with a display of her craft and her role as a mentor to the next generation of female artists. The mores of the time dictated that women should not call attention to themselves, and certainly not to their work, but the artist’s job involved hustling. Labille-Guiard’s self-portrait is evidence of this hustle, of her efforts to make her name known amongst the art circles. And like Anguissola did two centuries earlier, Labille-Guiard steadily locks eyes with the viewer, as if daring us to object.

After another hundred years, Russian artist Marie Bashkirtseff took a theme similar to Labille-Guiard’s and drove it even further. In 1881 she painted a scene in which a group of female artists are taking a life-drawing class — just like the ones women were barred from attending in the 17th century — and their model is a young man, instead of a young woman. By reversing the gender roles of the artists and model, Bashkirtseff continues the work her precursors began in paving the way for a new era of female artistry and portraiture.

Indeed, by the 20th century, female painters were ready to charge forward and include formerly taboo subjects like nudity and pregnancy, and even more transgressive, full-body self-portraiture in the nude. In 1906, Paula Modersohn-Becker painted a nude, pregnant self-portrait, her lower body covered loosely by a sarong, a small baby bump sitting just above it. Entitled Self-portrait on the sixth anniversary of marriage, the painting is a fiction. Modersohn-Becker was never pregnant; in fact, she was preparing to leave her husband right around the time she created the piece. The pregnancy seems to be metaphorical instead, her incubation of a personal and professional freedom she only gained when she left her domestic life behind for good.

Modersohn-Becker’s faux pregnant portrait, with her bare breasts, simple sarong, and the garland she is wearing around her neck, evokes the Tahitian women that Gaugin obsessively painted in similar poses and outfits. There is a big difference between Gaugin’s exoticized, objectified women, the ones he painted as the Other. Modersohn-Becker is not passive in her portrait, like Gaugin’s observed women. She takes that trope of the gaze and returns it, like her foremothers did before her, demanding recognition, visibility, and dignity.

How Self Portraiture Paved the Way for Raw Self Expression

It took all of those centuries, all of those female artists who had the courage to break the rules, to get up and hustle, and to put on the canvas the reality they would rather see, to set the stage for that other artist whose self-portraits are as recognizable as Rembrandt and Van Gogh’s: Frida Kahlo. Born in México, Kahlo was raised in a cosmopolitan family with a variety of cultural influences. She suffered from polio at the age of 8, which left her miraculously alive but with a permanently injured leg. A traffic accident in her teen years flung her deeper into a lifetime of spine problems, surgeries, metal orthopedic corsets, and a deep understanding of pain and vulnerability.

Though her career began with her being known as Madame Diego Rivera, Kahlo would eventually make her own name known through a series of self-portraits that mingled the trappings of her illness with the beauty of womanhood. Showing herself in a naturalistic way and often dressed in colorful, traditional Mexican garb, her hair braided in Oaxacan style, Kahlo reveals her weakened leg, her unibrow and faint mustache, sometimes even her medieval-looking corset. Her gaze, fueled by the cumulative strength of all the female artists before her who dared stare back, commands respect, appreciation for her craft, and most of all dignity. Beautiful, ill, strong, fragile, feminine, androgynous — Kahlo made it possible for all of the nuances of a real woman to be the attributes of an artist, too. After decades when her popularity soared, such that there are all kinds of Frida Kahlo-inspired merchandise for sale and my 7-year old knows not only her name but what she looks like, the Brooklyn Museum gave her a solo exhibit. Her dresses and personal effects were as big a part of the show as her art.

After Kahlo, female artists were able to continue exploring the fluid relationship between art and biography in the self-portraits. Loïs Mailou Jones Self-Portrait (1940) thematized the craft of painting, showing the artist equipped with multiple brushes and a canvas, and connects her painting to traditional African art that appears in the background. By placing herself in the cultural context that informs her art, Mailou Jones controls the narrative like men had for centuries.

It was perhaps the combination of photography, 1970s feminist art, and all of the groundwork laid by artists before her that finally yielded the kind of subversive female self-portraiture we needed in the late 20th century. Cindy Sherman wielded her camera like artists did brushes years before her. Choosing to represent herself in a variety of often contradictory ways, Sherman, like Kahlo, reinfects the full complexity of female-ness and femininity into her selfies. Portraying herself sometimes as passive and other times as being in the midst of it all, Sherman is always in control of the scene. Directing both the eye that peers through the lens and the object of that lens, Sherman’s art changed the way female artists understood their power to be in control, rather than mere object of the gaze.

Digital Self-Portraiture

Instagram is the perfect platform for this new brand of self-portraiture: it privileges image over text and gives the account holder complete control over what they display and who gets to see it. For artist Amalia Ulman, it gives her a canvas for her selfie “performance art,” a sort of millennial version of Cindy Sherman’s project, in which the artist photographs herself in an array of fictional personae designed to showcase the many aspects of women.

In 2019, we are all Ulman. We may not have yet achieved employment equality or erased the pay gap. We haven’t quite gotten to where we need to be. But thanks to the Anguissolas, the Kahlos, and the Shermans that preceded us, all we need is a camera and the right light to present the world with the image of ourselves we most want to see.

For Image credit or remove please email for immediate removal - info@belatina.com