Isabel Allende begins every book she writes on Jan. 8th.

Her first novel was begun on this specific date in 1981, and even though it didn’t start out as one, what came out of a letter that Allende sat down to write became pure alchemy. The book enjoyed wild acclaim and features characters who believe in—and embody—magic.

Allende has since written more novels, memoirs, and collections of short stories, each started on Jan. 8th, and I suppose the consistency of the practice works—she is insanely prolific. It seems to serve as an incantation, one that her characters would love, and with it Allende brings about each subsequent book with the same magic that her first one ignited.

Allende’s Roots

By the time Isabel Allende burst onto the literary scene with her 1982 tour de force novel House of the Spirits, her resume read as if she had already led several previous lives. Born in Lima, Perú in 1942 to Chilean diplomat Tomás Allende and his wife Francisca, Isabel, by the time Isabel was three, her mother left Mr. Allende and returned to Chile, where she raised her three children with the help of her father.

Her mother’s experience deeply marked Allende, who vowed never to be dependent on a partner for her livelihood. Isabel began to learn about shattering the conventions that society at the time imposed on women very early.

Back on her feet in Chile, Francisca married another diplomat, Ramón Huidobro. As a child of members of the diplomatic corps, Allende’s early education took her around the world. Attending international English-language schools in places like Bolivia and Lebanon afforded her a solid foundation in critical thinking and globalism. In spite of the language of her schooling, Allende always wrote prose in Spanish, reserving her fluent English for speeches and interviews.

Language and Magic

This feeling is not unusual in bilingual authors. Allende learned to use the English language as a tool to acquire more learning and to move through different cultures with linguistic common currency. For the work of the heart, though, she resorts to Spanish, both for her fiction and memoirs. It’s as if the magic spell of her brand of literature can only be effective when recited in her native tongue.

Even more impressive than this education Allende was given was what she makes of it. When I read Stories of Eva Luna as a new release while living in Bogotá, I never realized how far away in place and condition she grew up from the campesinos and guerrilleros she describes. In her fiction, Allende shied away from identifying setting, and this gave her the freedom to draw composite pictures, draw from numerous experiences, as well as to imbue her fiction with magical realism and her other prose with highly sensual language. Allende’s worlds are self-created, and sometimes also Chile and sometimes not.

Upon her return to Chile as an adult, Allende took her first job with the United Nations, working for the Food and Agriculture Administration for 6 years. In 1962, she married Miguel Frías, and their first years together resembled her own childhood, as the two traveled through Europe with their daughter, Paula. The family’s return to Chile coincided with the birth of their second child, a son named Nicolás.

The Feminism and Social Commitment of a Power Novelist

What follow are a series of endeavors that that speak to Allende’s commitment to social justice and the empowerment of women. She co-founded and wrote for Chile’s first feminist literary magazine, named, like her daughter, Paula. She ran a television program that was both comedic and political, and also featured interviews. For nearly a decade, Allende wrote prolifically, contributing columns to various publications, and producing two children’s books and a play entitled The Ambassador, all informed by her personal experiences.

Allende’s career as a journalist and television personality exploded in the mid-70s. We know she has the charisma, evidenced by her numerous interviews, public addresses, and TED talks. When her uncle, Salvador Allende was elected the first socialist president of Chile, the direction of her career was still within her control. But when in 1973 he was violently overthrown and died, the tectonic plates beneath Allende’s life shifted. She and her family were forced to leave Chile, where under the totalitarian regime she was suspect both because of her inclinations and her family of origin.

Allende emigrated to Venezuela with her family, and found work as a school administrator, a way to get her footing back in a new city. She was nearly 40 by then, and still not a writer by trade. She searched for work in journalism, which had been her bread and butter so far, but there was no work for her.

The Birth of the House of the Spirits

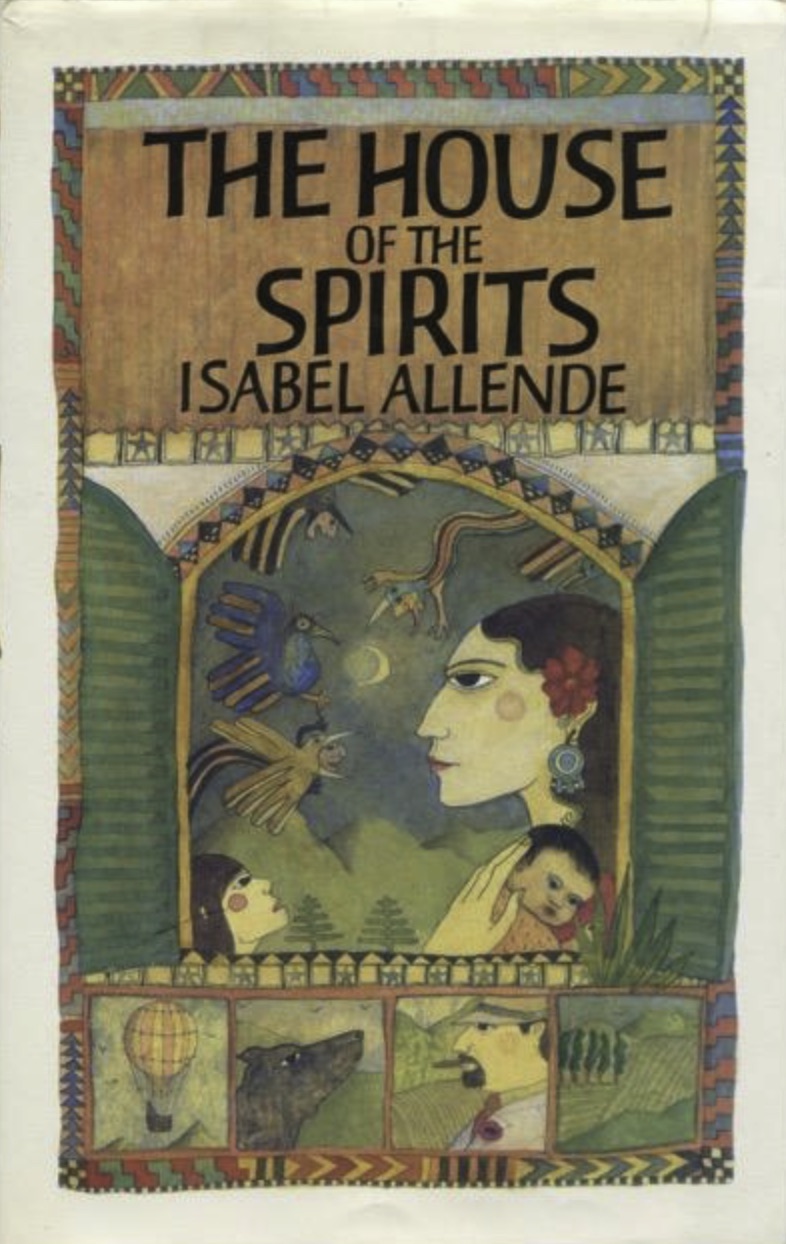

Allende’s marriage to Frías did not survive the move and neither did her beloved grandfather. News of his declining health reached Allende in 1981, made all the more bitter by the condition of exile. As per Allende herself, the intention was to write a letter to the man who helped raise her, to whom she would not get to say goodbye in person. Through that special magic of Allende’s and in a single year, what came out was a 500-page novel, The House of the Spirits.

She evokes a ramshackle mansion full of women and old furniture, matriarchs and secrets, a family saga entwined with ghosts. Unable to travel home in person, she was only able to bring Chile — her Chile — to life again through her creation of the fictional Trueba family. Allende’s protagonists are women through the generations, similar in name but distinct in character, strong, vulnerable, feral, each endowed with unique and sometimes supernatural talents.

Allende’s protagonists are women through the generations, similar in name but distinct in character, strong, vulnerable, feral, each endowed with unique and sometimes supernatural talents.

One of the salient themes of the book is revolution, the overturning of governments just as much as antiquated social conventions, and long-held unproven beliefs. The country it depicts could certainly be Chile, but it could also just as easily be a stand-in for Colombia, or Dominican Republic or Mexico or Venezuela, where it was written. It’s universality was part of its power. The House of the Spirits was an international bestseller with over 65 million copies sold in 35 different languages.

This period late 1970s and 80s were pivotal for Latin American literature, in that there was no unified concept before then. Extremely talented writers were working in tandem, in Argentina, Chile, Perú, Colombia, or while in exile in Paris and Madrid, separated by the giant mountain range of the Andes or the ocean and the lack of connectivity of that century.

But in the 80s, these threads of magical realism started to be woven together by European readers and literary critics, and suddenly there was this new genre — Latin American literature, often lumped together as magical realism. The writers all had in common good scholarship, erudition, and the use of fantastical elements, often used to divert censors from the underlying political commentary. These writers (García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Cortázar, Arenas) then became a virtual community before these even existed. All of these writers are giants in the field and they are all men except for Allende.

Allende’s House of the Spirits started her on the path to earning the well-deserved honor of being one of the most widely read Spanish-language writers in history. The accidental novel also opened the floodgates for Allende personally, who at the age of 40 suddenly reinvented herself. Set in another unnamed land of political oppression and civil unrest, Of Love and Shadows followed her first novel. Making the most of her exile, Allende was able to take this topic straight on without fear of repercussion, while in Chile the book would never have seen the light of day.

Allende’s widely acclaimed Eva Luna about a young girl and her misadventures arrived in 1987, the same year that her divorce from Frías became final. A rare example of a female bildungsroman, this novel presents a scrappy female protagonist who survives the unthinkable, from abandonment to abuse at various hands. Allende creates a rich universe for these characters, so much so that they spill over into a second narrative. Stories of Eva Luna, a quasi-sequel to Eva Luna that follows many of the same characters, appears in publication in 1989. All 4 of these first books are instantly well-received and widely translated.

Almost as if Allende’s real life were thoughtfully plotted by a masterful writer like herself, Stories of Eva Luna completes the narrative of her previous novel and turns out to be the epilogue on her time in Latin America. Allende, who admitted to having a girlish ease for it, fell in love with a retired lawyer-turned-writer Willie Gordon, and moved to California. Two years later, in 1990, democracy returned to Chile and Allende was able to visit her home country for the first time in 15 years. Allende wa appropriately awarded the “Gabriela Mistral Inter-American Prize for Culture,” named for the Chilean Nobel-laureate and diplomat Allende, the first of many awards she went on to receive.

Allende in America

Good authors write what they know, and once Allende became situated in North America, so did her fiction. The Infinite Plan, Allende’s first American novel was published in 1991. The writer might have been gearing up for another rapid succession of novels, but here she was instead derailed by the sudden illness of her daughter, Paula. Once again, Allende’s world, and because of it her art, was about to drastically change.

When Paula fell into a coma from porphyria while living in Madrid, Allende moved her to California to care for her in her home. This year-long nightmare did not have a happy ending and no amount of magic could keep Paula with her mother. A namesake memoir of Allende’s year and her daughter’s grueling experience was published in 1992.

A deeply confessional writer, it was nonetheless remarkable that Allende had the fortitude to write this tale while still so fresh. When even her mother remarks on her incredible vulnerability, Allende cites the strength she derives from the “exchange of emotions” that she has with her readership.

The next five years will proved to be a time when Allende would keep her magic closer to the vest. She describes the time after the death of Paula as “dark.” In the interim, House of the Spirits was staged in London, then made into a film starring Winona Ryder and Glenn Close (1993) and Of Love and Shadows is adapted for the big screen, starring Antonio Banderas (1994). Allende remained very much at the fringe of these productions and has said that she would not have chosen to be involved with either of the adaptations, citing her lack of knowledge of the media and the sense that she wouldn’t want anyone “looking over her shoulder” as she writes, either.

In 1996, Allende began to work directly with philanthropic and humanitarian efforts, creating the Isabel Allende Foundation in honor of Paula, to promote equality for women and girls around the world. (Perhaps this effort began the thaw for Allende, who continued to receive accolades for her work, including the Lillian and Dorothy Gish prize for the arts in 1998.

The grieving Allende continued living with Willie in California; her son eventually started a family and moved close to his mom. Slowly, the color came back to a life in black and white. Allende was able to see she was loved and supported, and the arrival of grandchildren brought her joy to do what she had already become good at — picking herself up and finding the way to channel the pain.

Novels Soldier of Fortune (1999) and Portrait in Sepia (2000) soon followed, Allende’s prolific nature rising again. She successfully tried her hand at young adult fiction, received accolades, too many to list. By 2003, Allende became a U.S. citizen and now writes more candidly than ever about Chile. The reception of her memoir My Invented Country, published the same year of her naturalization, has been widely followed, as it includes photos of family heirlooms and archival documents, while decrying the necessary absence from her homeland.

Honored, Praised and Celebrated

Honored by Chilean President Bachelet in 2013 and American President Obama, who awards her the Medal of Freedom in 2014, Allende also received honorary doctorates from Harvard University and San Francisco State University, as well as the highest award possible from the FIU creative writing program. Her novel House of the Spirits has received awards not only in her native Chile and adopted U.S., but in Denmark, Germany, England and worldwide. Allende has carried an Olympic torch, presented an opera along with Plácido Domingo. But most fittingly, she received the PEN Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016.

Isabel Allende has written more books in the last 15 years than in her entire career prior. Always a phoenix, her marriage to Willie ended a few years ago, but again she rises. Allende expresses no regrets about that relationship or any other, and remains open to the possibility of finding love again, if not marriage . Through it all, she has somehow managed to add 12 more titles to her bibliography, including The Japanese Lover (2015), a favorite read for book clubs and her most recent novel In the Midst of Winter (2017).

Allende’s inadvertent political work became a second career of sorts, as much as she avoided it. She continues to work on behalf of women, advocating for reproductive rights and progressive thinking in general. She is a champion of women, girls, and the underdog.

Her personal life is full with her family, friends and she is pleased to hear that the struggles she writes about, perhaps even her own struggles, have inspired so many of her readers to face similar hardships.

As much magic as Allende is capable of producing in literature and in her personal life, it is said that she feels disenchanted by the current political climate in America. She follows closely what happens here as well as in Chile and around the world, and is happy to share opinions on any subject she is knowledgeable about. Though she has admitted to never wanting to hold public office, the ever-morphing Allende could easily have another brand-new career as a political commentator.

In the meantime, I imagine her in California, reading to a lapful of grandkids or exploring the town with a new beau. What is certain is that Allende is showing no signs of being done just yet.

For Image credit or remove please email for immediate removal - info@belatina.com