In 1975, the APA (American Psychological Association) assembled a special task force to create a set of guidelines for the ethical treatment of women and girls. The committee was partly responding to the ongoing fight for civil rights, laying bare the underlying biases and stereotypes that govern so much of how we are held in society and the assumptions our culture makes about our capacities and limitations, based solely on our sex.

Making therapists aware of the gender-based discrimination and trauma a female patient likely experience in the world was one part of the work of this report. The other was enlightening psychiatrists and psychologists on their own complicity in the patriarchal structure that historically stereotyped — and mis-treated — women, pointing out their own underlying biases. As it turns out, the mental health profession owed us big time already for getting it completely wrong about women, straight out of the gate.

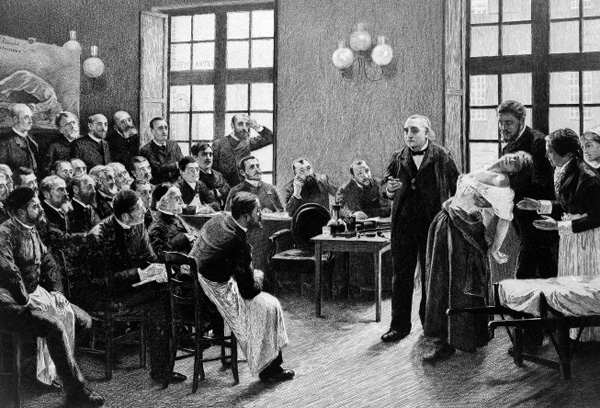

While psychiatry flourished as a treatment in Europe in the 1800s, our battle for equal rights wouldn’t begin en masse until a decade later, with the women’s suffrage movement and the first large-scale clamors for gender equality. So while mental health treatment was becoming a (voluntary) option for men, it was not something women reached for. Instead, mental health was a euphemism for a powerful weapon of the patriarchy. Controlling husbands, fathers, male doctors and psychiatrists had an ideal way to stop a rebellious woman in her tracks: calling her crazy.

The History of Psychiatry and Women

Psychiatry was used in the Victorian period as a measure for whether a woman fit the role prescribed for her and as her punishment if she didn’t. Stepping outside the homemaker role amounted to insanity and husbands were essentially given mental custody of their wives, whom they could commit to a sanatorium with a swipe of a shrink’s pen. Being unhappy with domesticity, one’s husband, postpartum depression, wishing to work outside the home, not wanting to marry or have children, and any sort of hormonal dysphoria amounted to insanity. Middle and upper class women were sent to institutions when they stepped out of line. Some were locked up in the attic.

So prevalent was the practice of over-diagnosing women with hysteria in the 19th century, a whole cannon of literature and film exists around the trope of the madwoman in the attic. From Jane Eyre (1847) to Rebecca (1938) to the film noir classic Gaslight (1944), cardboard-cutout female characters are the dark family secret, the melancholy past of the broodingly dark male protagonist now courting his fresh, young second wife. But are these women really mentally ill? Or are they tired of living in Gothic castles with eccentric and creepy men, isolated and bored out of their wits?

A classic of feminist literature that hinges on this tension is the 1892 story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” in which the narrator and protagonist is driven to actual madness by her husband’s (who happens to also be a doctor) decision that she has a nervous ailment and needs to rest in a yellow-papered room. Through the woman’s journal entries we see that she relates to her husband in a patriarchal way, that her volition is all but erased when she cannot choose what to eat, how to spend her time, or even which room she would like to rest in. He runs her days and she becomes mentally trapped. The ending is ambiguous, but one reading follows the writer’s descent into hallucination and depersonalization, perhaps a psychotic break, which is her only way out of that room.

Gilman, who was herself sentenced to a few months of “rest cure,” domesticity, and prohibited from working when she suffered from post parts depression, published the story under her previous married name, Stetson. Unwilling to lead a conventional life, she courageously divorced her first husband at a time when this was shameful, left her daughter in his care (even more shameful), and devoted her life to writing and lecturing, often about female financial independence. In 1935, diagnosed with breast cancer, Gilman chose to commit suicide. Her contribution to the feminist push that it would take to turn the tide of psychological services for women was to write this story, the least characteristic of her writings, to keep others from receiving similar treatments.

Enter Sigmund Freud

Meanwhile, in Europe, a young Sigmund Freud was striving to debunk his predecessor, Jean-Martin Charcot, who felt that hysteria was a female-only sexual problem corrected by…you guessed it: marriage. Freud, who probably had no patience for the clumsy euphemism, insisted psychological disturbances were not gender-coded and, at least in this case, neither would hysteria be solved by having sex. He brought the idea of the “talking cure” or psychoanalysis to the practice, so instead of diagnosing patients based solely on their gender and husband’s recommendations, now clinicians were listening to them.

Despite this marked improvement, there was plenty of work yet to be done. The chaos of two back-to-back world wars, during which mental health took a complete back burner to the reintegration of the men into society and the idealization of the original Betty Draper-type woman, was the flavor in the 1950s. As the civil rights movement, the sexual revolution, and college/hippie life started to take over the United States, the new Betty Draper emerged: a woman prescribed minor tranquilizers (Xanax, etc.) in order to cope with staying the course of her limiting marriage and conforming to the equally limiting feminine paradigm.

Tranquilizers only provided a bandage for what is inherently dysfunctional in our society, setting off the Stepford Wife-ing of the suburbs during the 1960s and 70s. Male doctors over-prescribed these medications to women, who were inherently dissatisfied with their lives, like their predecessors had wielded rest cures against disobedient women. Feminists continued to warn about the dangers of these sedative-type medications being a method of control, but we must thank both the advent of antidepressants and the continued benefits derived from actual therapy for easing us out of the (self-)medicating, Ice Storm era of the 1960s and 70s.

The APA Changes its Lens

Right around this time, the APA realized that just as their profession mistakenly pinned a bevy of other circumstances, causes, and underlying conditions on “female hysteria” for almost two centuries, now they had to change the lens so female patients could be heard and treated ethically. Their first set of guidelines sought to protect women from being misunderstood by the very person charged with helping them find mental well-being as well as protecting them from abuse at the hands of that same person. The idea was that by recognizing how sexism plays a role both everyday biases micro-aggressions against women, as well as negatively influencing our psychological treatment, therapists should be able to overcome stereotypes.

Even the therapists on that initial committee recognized that there would be a need to periodically review and revise the document. The new perspective on administering therapy to women without over diagnosing and gas-lighting appeared up-to-date until the early 1990s, when it became apparent that the guidelines needed a tweak. Specifically, girls needed to be addressed as well as women, certain prevalent conditions (like eating disorders) merited their own discussion, violence against women needed to be acknowledged a priori, and multiculturalism was essential to feminism. Rewrites in 1993, 1998, and the early 2000s revolved around the inclusion of diversity sensitivity and advocacy, as well as the first considerations of sexual orientation, and the challenges of older women.

Before this latest update to the guidelines, the APA had made good headway since the days of the abominable rest cure. Naturally, now that we know better we can do better. So while the 2007 version is careful to address the stressors that race, socio-economic status, and sexuality can add to women’s lives, the 2018 version also takes into account transgender people and a wider spectrum of sexualities. In the wake of #metoo, the guidelines also include the need to be sensitive to the immense trauma resulting from millennia of violence perpetrated against women in the forms of harassment, assault, and abuse. 2007 makes ample note that women are more likely to experience abuse than men, recognizing that we are also more likely to seek psychological help.

The update also makes the effort to be inclusive of military veterans as a group who experiences particular trauma, and of women and girls with mental disabilities in addition to physical ones (such as ADHD and autism spectrum disorders. In the true spirit of feminism, each revision (which should occur every ten years, within two years of that moment of expiration, or whenever new findings require it) strives to cast a wider protective net. Most saliently, while the 2007 devoted much of its language, including the first few guidelines, to articulating and acknowledging the problem of gender bias, the current ones begin with the steps towards a solution: recognizing women and girls’ strengths and “cultivating” them.

A Refocus on Inner Strength and Resilience

In fact, the bulk of the advice in the APA’s 2018 therapeutic approach is to be extremely wary of over diagnosing. Instead, the guidelines emphasize the therapist’s role in helping women channel our inner strength and resilience. Personally, clinicians are also encouraged to continue reflecting on embedded biases, personal ones, systemic injustices, and even environments hostile to the treatment of verifiable disorders in women. Geopolitical, social, economic, and other contexts will all continue to be taken into account when administering therapy, and there is even a call to make space for native or indigenous forms of treatment. However, the biggest message of the 2018 revision seems to hearken back to that original sin of psychotherapy — a stern warning against pathologizing, stigmatizing, and further marginalizing women and girls who seek psychological support.

Perhaps even more affirming that this revision, which some would say was a few years overdue, is the recently published first ever APA guidelines governing the treatment of men. This might sound ironic at first. In a world run according to patriarchal rules, why would men need a set of psychological guidelines made just for them? Examining the gender-specific biases and stereotypes that affect men and boys has led the APA to see the other side of the coin. Men have not been culturally encouraged to dig deep and feel their emotions. Unlike us, they suffer from the underdiagnosing of internalizing conditions such as depression, anxiety, and a treasure trove of stuff that disproportionately qualified women as hysterics. But instead of building men up to be strong, pragmatic, and unemotional, the APA has found that this social conditioning has contributed to a male ideology with underpinnings of misogyny and homophobia instead.

This is why we need to care about what’s going on with men, too. Their unchecked feelings lead directly to their treatment of us. The APA realizes the effects of the media and society on women and girls, leading to higher incidence of eating disorders and depression amongst us than men. It is equally clear that the prevalence of violent crime lies squarely on the shoulders of men. While the guidelines have long flagged women’s vulnerabilities, we finally are coming to terms with the idea that men are prone to a series of other factors and these affect our gender dynamics just as much.

Boys, for example, are more likely to experience bullying than girls and men experience pressure to carry on violence and antisocial behaviors in order to preserve their place in the pecking order. These factors all lead to men being more likely to be diagnosed with externalizing disorders (like ADHD), which require medication, than internalizing ones (like depression), which benefit from therapy. The ways in which our culture has wired men is to bottle up all those feelings but that doesn’t make them go away. Instead, it transforms them into something potentially damaging.

So while the APA is encouraging therapists to look more closely at what men are feeling and perhaps hiding from view, they suggest that women be reminded we already have a toolkit at hand. The coping mechanisms and resilience we have developed over millennia and across cultures are the same mechanism we can use to help us overcome the stressors that continue to stack the deck against us.

Each set of new APA guidelines begins with somewhat general remarks on how much society has changed in recent years and how those changes require the current revision. While it is certainly true that the role of women in society and the view society has of us have shifted, and especially so in the last handful of years, in some ways we have uncovered even more violence, trauma, and pain than some were ready to face. The guidelines don’t overlook that. The existence of that trauma and the strength we have shown in enduring it, surviving it, and then recounting it, informs the therapeutic recommendations of the APA.

Women have gone from being believed to be weaker and more prone to psychological problems than our male counterparts to being credited with naturally arriving at our own protocol. The men who once were our wardens are now being looked at as patients themselves, too. The APA’s new guidelines are kind of a compliment, a message of encouragement that if we persevere along this path perhaps we will eventually arrive at that place just beyond bias, where each mind can be supported in its own needs, regardless of gender.

For Image credit or remove please email for immediate removal - info@belatina.com